Why Coding Assistants are more than vibe coding enablers

Key Takeaways:

- Coding assistants significantly speed up initial development phases.

- Incremental, ‘human-based’ test driven development is currently most effective.

- Good version control practices, solid domain knowledge and clear, strategic oversight remain critical.

- Agents struggle with maintaining coherent style, design principles, and managing larger contexts – require human intervention.

Introduction:

I’ve been working with LLMs since April 2023, using them to power a simulated society (Willowbrook) to quantify the human-like-ness encoded within them. During that time, I’ve had GitHub Copilot enabled within my VSCode IDE and have occasionally tasked ChatGPT with a coding related question. But my use of these tools hasn’t evolved; the range of tasks I consider suitable and the way I engage with coding assistants hasn’t changed for over a year.

The recent paper from METR on HCAST Human-Calibrated Autonomy Software Tasks, stated that coding assistants can now autonomously do what would take a human up to an hour to do with over 70% accuracy, a statistic repeated in many forums, including by Matt Clifford the UK special advisor on AI [at the CETaS showcase in April]. So, I figured now would be a good time for me to jump in and explore what current coding assistants can deliver… and what I’m missing!

A quick caveat before we dive in: this post isn’t the result of a structured or methodical evaluation. Rather, it reflects my informal journey into using Generative AI e.g. large language models (LLMs) and agentic AI tools to write software, and my observations as someone who’s been a professional software developer for 20*cough* years. There will be tools I’ve not tried out, and there will be aspects of tools mentioned I didn’t explore.

For the last year, my interactions with GenAI based coding tools like GitHub Copilot have been a little underwhelming and somewhat frustrating. After the initial novelty period, GitHub Copilot’s auto complete suggestions begin to feel intrusive and were often inaccurate or irrelevant, as such they become more of a distraction than an aid. Especially those suggesting a function that sounds just like what you were looking for, only to have your hopes dashed on a hallucination induced runtime error. But they are useful for generating unit tests, and spotting edge cases. For more substantive problems, I have tended to use ChatGPT (and whatever the recommended model is for coding at the time), this works well for certain functions, e.g. generating figures and charts using MatPlotLib, where I don’t do that often enough to retain the idiosyncrasies of the API in memory, and only a little context is required by the LLM to provide a solution.

Figure: Although sometimes, GitHub Copilot does make me smile with its autocomplete suggestions.

Autonomous Coding Agent (REPLIT):

Inspired or perhaps challenged by some recent podcasts which touted some even more impressive figures for autonomous coding agents, I decided to try Replit Agent. I used the agent via their browser interface and free (Starter) trial. Falling back on something I knew, I tasked the agent with recreating the classic arcade game Pacman, directing it to use the pygame library. I assumed that the model would have knowledge of the classic game from its training data, so it’s effectiveness wouldn’t be necessarily linked to my ability to describe it.

Prompt: “I would like you to recreate Pacman, in python using pygame library. I would like a nice object-oriented design, which incorporates, for example a ghost.py base class for inky, blinky, pinky and clyde to inherit from.”

Within a few minutes the agent had generated a whole project full of .py files, with what looked very similar to my implementation, the ghosts inherited from a ghost.py file, there was a file to handle the board, one for Pacman/the player and one for the fruit, etc. Yet, despite this sensible start, the agent went on to fail spectacularly, unable to execute its code effectively within Replit’s environment.

After a few repeated attempts, including switching languages entirely (from python to JavaScript and HTML) it was not able to successfully run the code. The agent lacked sufficient awareness of its environment, such that it wasn’t picking up issues related to the libraries it was using (in this case pygame). Although setup to build and execute its code, it was (obviously, currently) lacking the ability to visually inspect the output, assuming that if the game didn’t return an error when run, the functionality was delivered successfully. However, a blank screen and exit(0) - didn’t quite meet my needs!

With this example the system showed little to no understanding of problems it was having, and as such, I didn’t push past this, I should have perhaps started a different project, but considering one of the stated use cases was game development, I didn’t feel I was pushing the envelope of what it should have been able to cope with.

Cursor: Human-Based, Test-Driven Development!

My next experience, however, changed my thinking. Using Cursor The AI Code Editor, an environment based on VSCode, I tried again with the Pacman task. However, this time, instead of jumping in and writing it all, Cursor’s AI assistant encouraged me to adopt an incremental, step-by-step approach; the first step was to display Pacman and have him be controlled with the cursor keys. This system doesn’t try to run the code itself, instead it leaves running and evaluation to the user.

What emerged was a collaborative dynamic which I’d describe as “human-based test-driven development.” Each incremental piece of functionality; walls, ghosts, and interactions, was implemented by the AI, but tested and validated by me. Together we added the walls, pips, pills, the tunnel, the ghost hut and then one ghost at a time, with their specific pathfinding algorithms. The agent even suggested (asked) if Pinky’s pathfinding algorithm should include the original bug, where the location she targets is off by 4! Within a few hours we had a working version of Pacman, scores and all.

Out of approximately fifty incremental additions and iterations, only three resulted in syntax errors. In such cases I simply copied the error to the chat window and Cursor fixed the problem.

The code became irrelevant…

The way the cursor agent shaped the ‘collaboration’ meant that my role shifted from writing code or even reviewing changes, to guiding it to incrementally deliver functionality. The code became irrelevant. The cycle of asking Cursor to add a piece of functionality and then me running the code, and giving the AI feedback on how it performed, things that needed to be fixed, or directing it onto the next piece of functionality to be added, meant we managed to get a working Pacman game up and running within hours.

Observations:

-

Maintaining a clear vision of the intended functionality is vital (with Pacman that was easy). As the user’s role shifts from implementation to strategic direction. This way of working was, at first, quite alien to me… but didn’t take long to ‘let go’ of the code. A large part of that shift is linked to trust in the agent’s competence. In the case of Cursor, that trust built up fairly quickly given the first hour or so, during which time the agent generated solid, reliable code.

-

Occasionally, the AI stumbled, especially with more complex(subtle) bugs. It would often flick-flack between conflicting solutions or add unnecessary statements. Recognizing this downward spiral required careful judgment, and sufficient programming experience.

-

Good revision control behaviours become very important, I’ve never committed code so often for such small changes. But given point 2, the ability to revert to a known good state is critical.

-

Also linked to 2, is knowing when to Intervene: Crucially, my understanding of the problem space allowed me to identify precisely when to step in and stop the AI from making things worse, which would have resulted in a more messier and therefore increasingly fragile codebase.

-

Like other LLM based systems, Cursor wasn’t great at knowing when to give up. A lot like LLMs waxing lyrical when asked to describe a blank image. The system’s ability to know when to ask for help, is currently elusive.

-

Towards the end of the session, the agent seemed to get less accurate and therefore slightly less effective, I put this down to the code becoming too large, and although not hitting a system limit, it was likely hitting the LLM’s context limit (or associated attention issues), for example if a fix required refactoring it started to miss changes that should be made in other class/files. Although quick to fix, once highlighted.

-

As it reached the limit described above, the need for me to step in and debug the system happened more often, which was made more difficult due to the unfamiliar code. So, the process gets to the point where the user needs to ‘take back’ control/ownership of the code to enable better manual debugging for more complex problems.

-

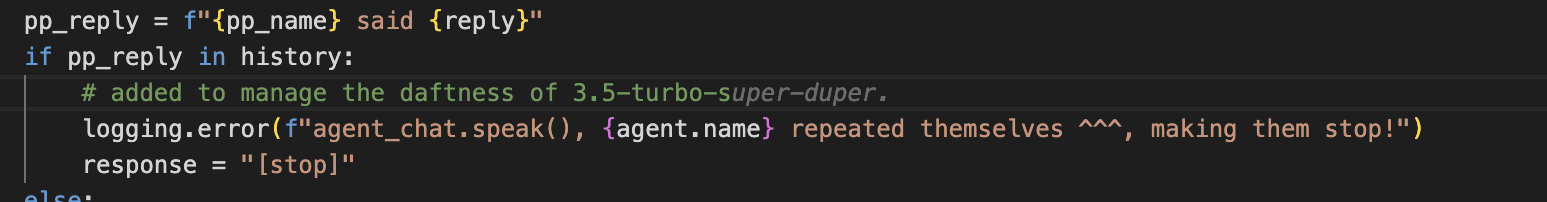

I found that taking back control of the code, required a fair amount of refactoring. The agent doesn’t have a consistent style or set of informal patterns that it stuck to. It also didn’t write code that ‘aligns’ with the flavour/style of existing code (a technique which sets good programmers apart from others). And sometimes it didn’t respect good design principles; at one point it had generated an overly long function, which had multiple responsibilities. It’s also not very good at cleaning up code which is made redundant when it fixes things.

-

Asking it to describe a change it’s about to make helps you gauge whether it’s understanding your directions. Asking it to describe existing code, has the added advantage of whilst it’s doing that – it ‘rubber-ducks’ itself often finding things to fix or improve as it goes!

The common analogy is that coding assistants are keen interns that can do the basic stuff well but need guidance. I don’t think that sits right (and does interns a disservice). These tools are useful, but I don’t think there is a human analogy, that captures the strengths and weaknesses well enough. The agent delivered functional code, and delivered it well, it met my requirements, and the code was well presented, i.e. good variable names and nearly always right (ran without failure) first time. But there are aspects of coding that are almost unwritten guidelines that (good) human programmer’s stick too. Implicit design patterns for the ordering of functions, the removal of dead code, the consistency of interfaces and functional patterns. What Cursor provided (before I took back control) was a blanket which comprises a patchwork of functional code. What I did was fix the stitching and rearrange the pieces into a blanket which didn’t hurt the eyes! Perhaps more importantly, I refactored the code so I could more easily spot future errors and maintenance issues (technical debt management!).

The new VSCode update (release notes), provides support to allow developers/users to specify their preferred coding standards and style preferences they expect the agents to adhere to. Whether this additional information distracts the LLM too much will be interesting to see.

After my Pacman experience, I used cursor to rewrite Willowbrook - don’t tell the bosses ;) I wanted a new simulation that ran faster. Using Cursor I created a new system, which centred around an event pump and async calls to the LLM. This system runs significantly faster than the previous version. Again, within a couple of days the simulation was running with nearly all the functionality of Willowbrook1 (which took significantly longer than two days to develop!) It took another day or so to ‘take back’ control and tidy the code. This task was less well known to the agent compared to Pacman, as was evident by the first few iterations of trying to pin down how to handle time passing in the simulation, but the programming concepts used; async calls in python (servicing events etc) would be fairly common within its training set. Again, the number of runtime errors was small, the speed of incremental develop was impressive. This time, Cursor added ideas into the code I had not considered; which I have left in to evaluate (hey, it’s research not production code!)

In both cases once the core design was implemented, and the code was taken back under my control, the way of working with the agent changed; small specific changes were requested, guiding the agent on how and where to make the changes, or asking the agent to describe the changes before making any alterations. Even then, committing often is a necessity, as occasionally the agent will decide a bigger change is required than I anticipated (often because of unclear directions or just because LLMs do that!).

Conclusions/Key points:

- When starting something new, these agents can offer significant time savings at the start of a project.

- ‘Human-based test driven development’ as a way of working is IMO the best strategy for getting the best out of the agents at the moment.

- Developers should try out these models on projects they are familiar with (but don’t forget to commit everything first!)

- If in a professional setting, the amount of effort put towards taking control of the code, should be the same level of effort you would dedicate verifying a 3rd party module of code or library randomly found on the internet! The responsibility for its correctness and conformance to non-functional requirements is with you.

21st May 2025, Dr Sarah Mercer.